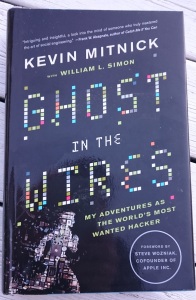

I recently finished reading Ghost in the Wires by Kevin Mitnick. It is the story of Mitnick’s hacking career, from the start in his teens, through becoming the FBI’s most wanted hacker, to spending years in jail before finally being released. It’s a fascinating book that at times reads like a thriller. One of the things that struck me when reading it was how often he used social engineering to gain access to systems. Here are three examples of what he did, and what we can learn from them.

I recently finished reading Ghost in the Wires by Kevin Mitnick. It is the story of Mitnick’s hacking career, from the start in his teens, through becoming the FBI’s most wanted hacker, to spending years in jail before finally being released. It’s a fascinating book that at times reads like a thriller. One of the things that struck me when reading it was how often he used social engineering to gain access to systems. Here are three examples of what he did, and what we can learn from them.

Getting Phone Bills

At one point, Kevin is suspecting that another hacker is working for the FBI. All he knows about him so far is his name, Eric (which may be an alias), and his cell phone number. He wants to learn more, so he finds the name of the store that sold the phone and subscription. He then calls them, giving the phone number and asking for more information about “his” account:

“What’s your name sir?” the lady on the other end asked. I told her, “It should be under U.S. Government”, hoping that she would be helpful enough to give the name on the account. She did. “Are you Mike Martinez?” she asked. “Yes, I’m Mike. By the way, what’s my account number again?” She wasn’t the least bit suspicious, and just read off the account number for me.

This was a pretext call, to gather information to use in the next step. Kevin called the store back, but the same woman answered, so he just hung up. He waited a while and called again. This time a man answered. Kevin pretended to be Mike, and gave the name, phone number and account number.

“I lost my last three invoices,” I said, and asked him to fax them to me right away. “I accidentally erased my address book off my cell phone and I need my bills to reconstruct it.” I said.

Within minutes, Kevin had the invoices. Each of the three monthly bills were nearly twenty pages long, listing well over a hundred calls. Many calls were to the Los Angeles headquarters of the FBI.

Getting a Password

A little later, Kevin is trying to get the dial-in number and password for PacTel’s billing system, in order to check out Mike’s calls further. He started by calling PacTel’s public customer service phone number. Claiming to be from the internal help desk, he asked:

“Are you using CBIS?” (the abbreviation used in some telcos for Customer Billing Information System). “No,” the customer service lady said. “I’m using CMB”. “Oh, okay, thanks anyway.”

Knowing that they use CMB lends credibility to the next step. Kevin now called the internal telecommunications department, giving the name of a manager in accounting that he had previously obtained. He said that he had a contractor coming to work on-site who needed a number assigned to him so he could receive voicemail. The voicemail account was set up, and Kevin recorded the message “This is Ralph Miller. I’m away from my desk, please leave a message.”

Next he called the IT department and asked who managed CMB. It was a guy named Dave Fletchall. He also found out the name, Mimi, of the secretary at that department. Then he called Dave, posing as Ralph Miller:

“What’s your callback?”. I gave him the internal extension number for my just-activated voicemail. When I tried the “I’ll be off-site and need remote access” approach, he said, “I can give you the dial-in, bit for security reasons, we’re not allowed to give passwords over the telephone. Where’s your desk?” I said, “I’m going to be out of the office today. Can you just seal it in an envelope and leave it with Mimi?”. He didn’t have a problem with that. “Can you do me a favour?” I said. “I’m on my way into a meeting, would you call my phone and leave the dial-up number?” He didn’t see a problem with that either.

Later in the day, Kevin called Mimi and said he was stuck in Dallas, and asked her to open the envelope Dave Fletchall had left for him and read him the information.

Getting Source Code

From the book it is quite clear that Kevin never hacked systems for financial gain. Instead, he did it just for the challenge of getting in. Often, he broke in to systems in order to get the source code for various operating systems and cell phones. When a new NEC phone came out, he decided to try to get the source code for it.

By making several calls to NEC’s U.S. subsidiaries, he found out that the cell phone software was developed at the Mobile Radio Division in Fukuoka, Japan. He called them, and the receptionist found someone who spoke English that could translate. Kevin notes that having a translator is a big advantage. The translator is right there, in the same company as the target, and speaking the same language. Also, people tend to assume that you have already been vetted if you are speaking through a translator. Via the translator, Kevin spoke with one of the lead software engineers.

“This is the Mobile Radio Division in Irving, Texas. We have a crisis here. We’ve had a catastrophic disk failure and lost our most recent versions of the source code for several mobile handsets.” His answer came back, “Why can’t you get it on mrdbolt?” Hmmm. What was that? I tried, “We can’t get onto that server because of the crash.” It passed the test – “mrdbolt” was obviously the name of the server used by this software group.

When Kevin asked if they could FTP the software to him, they balked, because they didn’t want to send this sensitive data outside the company. Saying that he had to take an incoming call and would call back later, Kevin got off the phone on organized another way. He would use another NEC subsidiary in the automotive sector as an intermediary. He called them and explained that they had network difficulties between Japan and Texas, and asked if he could set up a temporary account to FTP files to. No problem – he got the host name and log-in credentials while waiting on the phone.

Next he called Japan back. They had no problem with FTPing the files to a server within a NEC subsidiary. He then called the automotive subsidiary back and asked if the files had arrived. Because the way he had set it up, they assumed that Kevin had sent the files, so they helped him transfer the files to him.

Lessons

These are just three examples out many from the book. I really liked seeing them like they were presented in the book: in the context of what he was trying to accomplish, and with dialogue. They show how powerful social engineering can be. There are several themes to how he managed to get the information he wanted. These are worth noting to avoid falling for social engineering attacks:

Names and jargon. By using names of actual employees and departments, and the names of internal systems as well as other technical terms, he passes himself off as an insider. Once he has “proven” that he is from within the company, people are much less suspicious of his requests.

Multiple steps. In many cases, Kevin operated in several steps. The first step was usually to find out names or other information that could be used to provide authenticity in the later steps. Every bit of inside information helps.

People want to help. In almost all cases, Kevin uses a story where he has a problem that he needs help with. The server has crashed, or he is off-site and needs access to the system, or he accidentally deleted his address book. This works because most people want to be helpful.

In addition to containing many excellent examples of social engineering, Ghost in the Wires is an exciting and interesting story of one of the most famous hackers of all time, so I can really recommend it.

Discussions on Reddit, programming: https://redd.it/3yducn social engineering: https://redd.it/3ydzrd

Hacker News discussion: https://news.ycombinator.com/item?id=10796950

Pingback: Java Web Weekly 1 | Baeldung